It was as if I had no choice, really.

- I have a sci-fi podcast.

- I have been playing Moby Dick, or The Card Game.

- I have been playing Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag.

- And let us not forget Artemis.

You see, I had to write about space whaling.

Moby

The Moby Dick game is brilliant. It is beautifully done, for starters, with a depth of artistic detail which makes the game a must-own for anyone who decorates their home with old papers, faded prints, scraps torn from books. You know who you are. Every single one of the cards is worthy of matting, framing, and displaying in a prominent locations around your home, library, book-store, boathouse, or secret society lair, as is the box itself.

All that aside, though, it’s the deft creation of a particular feeling which makes the game notable in this case. This is not a game about beating the odds, forming a briliiant strategy, or fooling your opponents, though these skills certainly come in to play. In this game, you combat the constant feelings of dread as you lower down to hunt a whale, and shore up your defenses as best you can against the inevitable face-off with the great beast himself. In the rounds I’ve played, the term “bleak” has come up several times. You’re a whaler — you’re as likely to die as not from thousand varieties of bad luck. And the captain is driving you towards a near-certain doom.

At what low value was held the whaler’s life. The player feels a detachment from the lives of the crew. They’ll all end up dead anyway, often even before facing Moby Dick himself; best not to grow too fond. And what an unusually various crew it is. Men from all over, regardless of race or creed, hauling alongside each other where on land they would not be allowed to eat at the same table.

It’s about risk and reward and risk and risk. And these elements translate very well into a space-faring adventure.

Black Flag

Where the card game is about staving off despair in a merciless world, whaling in Black Flag is about high adventure and bare-chested virility.

Here, the feeling is excitement. You won’t die if the whale attacks you. A snapped line doesn’t whip anyone’s arm off. You want to land that harpoon throw and reap the rewards, Caribbean sun beating down on your back. It’s… a lot of fun.

Side note: I felt substantially more guilty for killing a whale than for plundering dozens of ships. Odd.

Again, even as you glory in the thrill of the hunt, you feel as if whale oil must had value far beyond gold or jewels to be worth its pursuit. And again, why would this not translate to the emptiness and danger of space?

Artemis

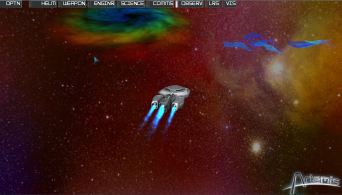

Tell me you’ve played this. A fantastic, home-grown spaceship simulation game which hooks everyone who touches it. My first experience with it was at a gaming convention, where the developer helped players through the basics and let us cruise around. And that’s when I first came across the rare space whale.

A fun addition to the game, almost an easter egg. You don’t get anything for finding them, or indeed for shooting them down. They’re just there, making their way through the emptiness.

And they’re beautiful.

From the Void

With all of this percolating in my headspace, it was only natural my protagonist would find himself on the hunt, facing one of the great dangers of the nullity for a chance at a share of the valuable nano-oil which can only be found in the skull of the voidwhale.

Check it out if you want, and I’d love to hear what you think. You can subscribe here, too.